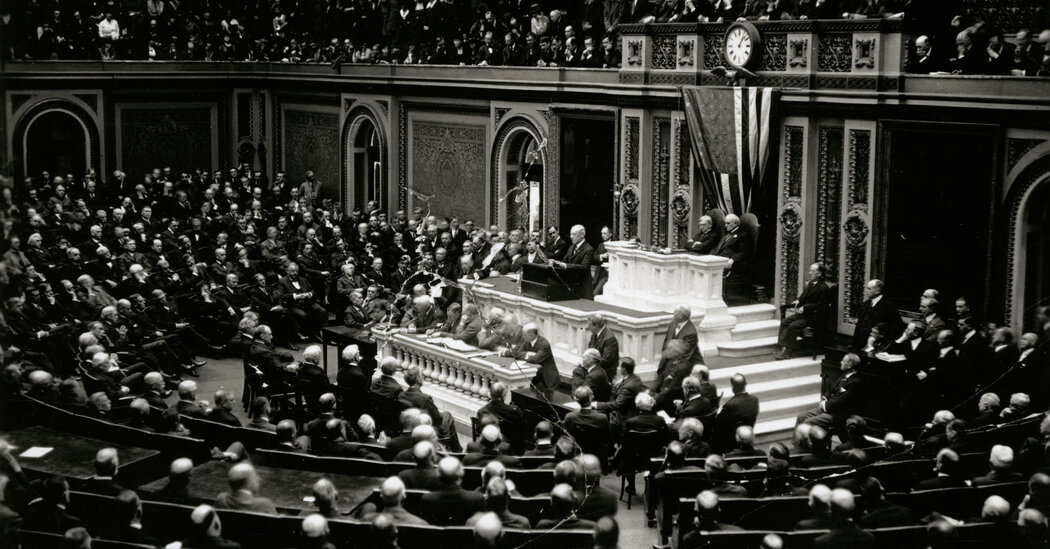

More than a century ago, Woodrow Wilson gave the first in-person presidential address to Congress since Thomas Jefferson ended the practice in 1801. The new tradition stuck and eventually became the template for the president’s annual “message to Congress.” It was Franklin Roosevelt who coined the phrase, “the State of the Union” in one of those speeches, and by the late 1940s, it had become our national shorthand for the speech. The 20th century transformed what had been, for most of American history, a staid, written report into a giant annual spectacle of presidential majesty and congressional hooting and hollering.

In recent years, thanks to the increasingly commingled worlds of politics and popular entertainment, the annual State of the Union address has evolved into an even grander and creakier spectacle: a nationally broadcast circus of government whose uncanny resemblance to an awards show or grand fund-raising gala has only grown as its cast of characters expanded. Today, the State of the Union functions as a kind of political Super Bowl, Oscars, Met Gala and Rotary Club dinner all in one. As self-serious as amateur theater and as monumental as a coronation, it is one of the weirdest evenings in American life. Only habituation makes it seem normal, and even habit has its limits.

National politicians have always had a kind of fame, but the rise of social media thrust politics into a realm of popular celebrity and turned the campy solemnity of the State of the Union into mere farce. Even the lowliest members of the House of Representatives used to sit at some statesmanlike remove from us, democratic avatars of actual constituencies, yes, but also a kind of abstraction. Now, via social media, we are privy to their passing thoughts, their workout routines and workplace rivalries, their classical American infatuations with crackpot theories. There was once something edifying and even a little mystical about virtually the entire American national government gathering in one place for a grand and unabashedly imperial spectacle. No longer. It has all the mystery and half the charm of a slapped-together awards show, a too-familiar crowd of celebrities who spend the evening alternating between looking overly enthusiastic and terribly bored.

For most of the past century, presidents have given the address in January or February. President Biden’s has been postponed until March. This delay has been attributed to the Covid pandemic, to the ratings competition of the Winter Olympics, and to the hope that last-minute politicking might rescue a few pieces of Mr. Biden’s legislative agenda from obdurate Republican opposition and the dogged lack of cooperation from Democratic Senators Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema. This hope is almost certainly doomed. Mr. Biden will march down the gauntlet of glad-handing members of Congress with his approval ratings at one of their lowest points, a tenacious pandemic, national worry over rising prices and a generally poisonous national mood, not to mention a terrifying Russian invasion of Ukraine that the administration and its European allies could predict but not forestall, and whose course could become more volatile and unpredictable.

A rival nuclear power starting a shooting war in Europe just a few days earlier presents the kind of circumstance in which a State of the Union address could hypothetically be vital. But it is still likely destined to merely be bland news cycle chum. The chatterboxes on the cable channels and the pundits in the political press will debate the “expectations” for the speech, and we will all earnestly pretend to wonder whether our president — older now than Ronald Reagan was when he left office — will be able to summon some heretofore unobserved rhetorical genius to conciliate our sick and tired nation.

I hope that he will subvert expectations deliberately. Mr. Biden’s intrinsic political genius is his ability to act as a mourner and as a bearer of bad news. His greatest act of political bravery was to tell America, after 20 years of lies, that the war in Afghanistan was over and lost, and then to mostly keep quiet and stick to his guns. The stakes are much lower for a gaudy speech like the State of the Union, but he should really do the same. Go up the hill, deliver a dull litany of bullet points, get to bed early and consign this silly ritual to C-SPAN, where it belongs.

In 1796, writing to his great friend, Filippo Mazzei, an Italian physician, farmer, pamphleteer and gunrunner for the American Revolution, Thomas Jefferson complained of the great changes in America since its independence. “In place of that noble love of liberty and republican government which carried us triumphantly thro’ the war, an Anglican, monarchical and aristocratical party has sprung up,” he wrote, lamenting the adoption of British “forms” of pomp and circumstance, especially by the executive and judicial branches. Mazzei’s enthusiasm overcame his discretion, and he promptly dispatched copies of Jefferson’s observations to friends around Europe. They were published in French and Italian, and then made their way back across the Atlantic to the United States, where they reputedly caused a personal rift with George Washington, whose regal presidency — complete with annual addresses to joint sessions of Congress, which Jefferson considered far too similar to a British monarch’s “speech from the throne” — was understood to be a target of Jefferson’s contempt.

Jefferson’s dream of a nation of independent yeoman farmers was a fantasy even in his own time (not to mention a bit hypocritical — can anyone imagine the squire of Monticello driving a horse and plow through 40 rocky acres of Appalachian Virginia?), but his hostility toward the monarchical trappings of an imperial presidency was not wrong. His dream would be undone as America became a continental empire, then a hemispheric power, then an overseas empire and a great industrial and military titan. The centrality and power of the presidency could only increase as America evolved into a modern, bureaucratic state. It was inevitable, with the advent of modern mass broadcast communications, that the president would become a figure of enormous cultural significance as well. By the 1930s, presidents were everywhere on the radio; by the 1960s and the gilded, media-centric presidency of John F. Kennedy, they were culturally ubiquitous, singular synecdoches for America itself.

We are too close to these people now. Pomp can stand a little silliness; it may even require it. But it can’t survive absurdity. The advent of social media ruined celebrity by imitating proximity, and the transformation of politicians into ruined celebrities further destroyed politics. To see an actor whom you only know from movies and glossy magazines glide down a red carpet once or twice a year in a wild dress and borrowed jewels is to be astonished; to live with her everyday eructations of bad musical opinions and worse food photographs is to be annoyed. Likewise in politics. Our ostensible leaders are social media addicts like the rest of us, only more so. Their court rituals and pagan traditions have lost all of their high masonic mystery. We find ourselves watching a regional industry dinner, the sorry spectacle of insiders wallowing in self-congratulation over rubber chicken amid too much applause.

The form is exhausted. Mr. Biden has largely avoided the more ostentatious imperial vibes of his office, in part because he is the least telegenic president since George H.W. Bush. He has none of Ronald Reagan’s actorly charm; he cannot mimic Bill Clinton’s gregarious air of a debauched but beloved country preacher; he lacks Mr. Bush’s jingoistic cheerleading, Mr. Obama’s grandiosity, Mr. Trump’s nasty but effective comic timing. If he were wise, he would embrace his relative plain-spokenness and dislike of spectacle and diminish this absurd tradition.

The founders themselves imagined a new constitutional convention every few generations; perhaps every hundred years is also a good time to come up with new binding national political rites. We could do away with the speech entirely, and simply give out more civic medals for ordinary workers — the supposedly essential Americans whose daily, unseen labor makes the country run even as they are steadily alienated from mass politics and the highflying economy. Otherwise, the speech will continue to be more tendentious, reality-show entertainment. Will Sam Alito mouth off again? Will Nancy Pelosi do another ironic clap? Who will leap to applaud which lines, and who will sit on their hands? Enough is enough. Make the State of the Union boring again. We have been sufficiently entertained.

Jacob Bacharach (@jakebackpack) is the author, most recently, of “A Cool Customer: Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.