It started with a weekday interview in an office near the Moscow River. The man was a murderer, it was said, but when I asked about the crime, he smirked and said he was framed. I remember his shoes, pointy and shined like glass.

I published a lot of articles as Moscow bureau chief for The Los Angeles Times, but this is one story I never wrote: About the problem that began with that 2008 interview and unfolded gradually over years — slowly enough to create the illusion that nothing was happening.

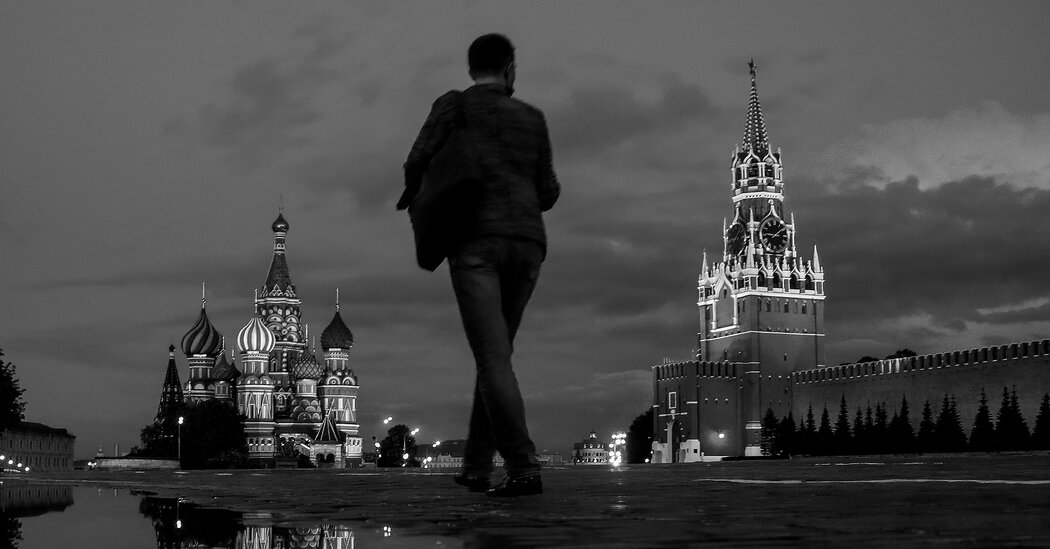

Russian power has a tendency to work that way. You detect a suggestion of a threat, but then it just lingers, unrealized, until finally you shrug it off. What I learned reporting on Vladimir Putin and his Russia is that, maybe sooner but more likely later, it will happen. And once it does, you think: Just as promised, nobody made a secret of it.

In 2008 there was speculation about a war in Georgia, and then it came. The bombing had hardly quieted before a new rumor moved through Moscow: Ukraine is next; he’ll take Crimea. The Russian military invited reporters on a junket to Sevastopol. We saw Russian graves tended by Russian priests, a Russian guided missile cruiser, Russian tourists on every corner of what was then a Ukrainian city. The sea had swallowed centuries of Russian blood; the sun was clear and bright. It was hard to write the story afterward because nothing actually happened. It was only a message: This place is rightly ours. Six years passed before Mr. Putin seized the peninsula.

By that time, I had slipped as quietly as possible out of Russia, having already accepted that hatred of the West and of the West’s collaborators was not a sideshow or an occasional propaganda point but the very foundation of Mr. Putin’s rule. It wasn’t only a deep hunger for Russian empire; there was a desire for vengeance, too. I didn’t arrive in Moscow with this understanding. I gleaned it gradually from conversations in Kyiv and Warsaw and Irkutsk, reporting under Russian bombardment in Georgia, peering out from Moscow to regard the world from that frosty vantage.

Mostly I learned because, as an American reporter, I was both object and tool of this institutional hatred.

*

I was not particularly important to the story I’m telling now. I stumbled into it. There were only two essential characters. Both were famous Russian men.

One was accused of murder.

The other would end up being murdered.

The purported killer’s name was Andrei Lugovoi. He’d been a K.G.B. bodyguard, and had visited the White House on state visits. In 2007 he was accused of killing the former Russian intelligence official and defector Alexander Litvinenko, who drank tea spiked with radioactive poison in a London hotel. With the British demanding his extradition so that he could face a murder charge, Mr. Lugovoi stayed in Russia as a luxuriously kept fugitive from justice. He wore impeccable suits in plush rooms and posed for photographs with admirers. He won a seat in the Russian Duma, the lower house of Parliament, which provided him with immunity against criminal prosecution and increased protection against defamation. In 2015, Mr. Putin awarded him a medal for “services to the motherland.”

I interviewed Mr. Lugovoi on a dim, snow-crusted winter morning. He sprang easily to his feet, eyes darting, posture firm. I asked about the poisoning. He smiled and said, vaguely, that he’d been framed, then spoke longingly of the Soviet Union and sneeringly of the United States and its British “tool.” We Americans foolishly believed we’d beaten Russia, he intimated, but our self-congratulation was premature.

“I don’t agree that the Cold War is back,” he said. “It never ended.”

I heard this a lot. Most Russians I met couldn’t fathom that Americans had psychologically relegated the Cold War to history, brushing aside outdated tensions to make room for fresher fears and new enemies. Nor could U.S. leaders of that time seem to grasp the extent to which Russia was still fixated on the same handful of grudges, stung and distrustful over the humiliation of the Soviet collapse and the perceived treachery of NATO expansion.

In this landscape, it was a triumph to be accused of murdering a Russian defector in one of the great capitals of Western empire. Georgia and especially Ukraine must be brought to heel; the empire would rise again. Russian glory and American ruin. Or perhaps better to say, Russian glory by way of American ruin. It wasn’t enough for Moscow to rise: America should pay.

Mr. Lugovoi’s tone kept getting colder. When I mentioned revenge, he laughed mirthlessly, then spoke deliberately.

“I don’t agree with this biblical saying that if they hit you on one cheek, you should turn the other cheek,” he said. “If they hit you on one cheek, you hit them back with a fist.”

My profile of Mr. Lugovoi ran on the front page, and I braced myself for complaint. But he seemed delighted to be portrayed as a hardened murder suspect. His office phoned to request extra copies.

*

The other famous man was Boris Nemtsov: physicist, politician, early adopter of the internet, adviser to a Ukrainian president. A protégé of Boris Yeltsin and relentless critic of Mr. Putin, Mr. Nemtsov would eventually gather evidence of Russia’s covert military adventures in Ukraine.

I interviewed Mr. Nemtsov often. Many Moscow correspondents did. He held court in the chambers of one of Stalin’s iconic Seven Sisters skyscrapers, armed with stashes of documents and memories.

There was something elfin in his face — bright snapping eyes and a plump-lipped, gaptoothed grin. He was articulate and almost unbelievably knowledgeable, and his conversation was more monologue than small talk.

At the time, Russia was getting ready to host the Olympics in Mr. Nemtsov’s hometown, Sochi. He had announced his candidacy for mayor, unable to resist the chance to simultaneously boost his own profile and yank Mr. Putin’s chain. His competition included a porn star, a ballerina and possibly even Mr. Lugovoi, the maybe assassin who was considering running. I decided to write a quick feature about the many would-be mayors of the Sochi Olympics.

A year had passed since my interview with Mr. Lugovoi, but I was still in his good graces, and we met for another interview. He wore a pale pink oxford so exquisite, it made me think of that scene when Daisy weeps over Gatsby’s shirts. Once again, he held forth on politics: The evils of the United States and Britain, which he collectively called “the Anglo-Saxon empire.” The irrelevance and hypocrisy of Britain. “They pillaged their colonies and then went back to their own tiny island and said, ‘Now we’ll be a democracy,’” he said. Then he told a rambling and antisemitic anecdote.

“We call it some kind of Jewish basketball,” he crowed at the end of an incomprehensible story about a Jew selling an elephant to another Jew.

I stared at him.

“People here understand it,” he shrugged.

I asked him about potentially running against Mr. Nemtsov.

“Such people have no place in Russia,” he said, his voice placid.

“When they say they want the best for the Russian people, as a man, I want to kick them in the head. I despise them. I despise them as miserable creatures.”

Mr. Nemtsov was campaigning in Sochi, so I called him on the phone. He said local television channels had refused to cover him. Police broke up a campaign meeting at a local theater. I asked what he thought of the prospect of Mr. Lugovoi, the accused poisoner, running for mayor.

“He’s a K.G.B. guy, so I’m sure the decision had to come from the Kremlin,” Mr. Nemtsov snapped. “They just come up with this clown, this murderer. It’s a disaster for Russia.”

I quoted both men in the article. The election was won by a candidate from Mr. Putin’s United Russia party.

It wasn’t until months later that the police demanded my notes.

*

When I heard that the police had phoned the bureau to request my notes from an interview with Mr. Nemtsov, I laughed. “Absolutely not.” But the police kept calling. They wanted those notes. They told me I’d have to testify if they went to trial. I kept saying no. I hoped they’d go away.

I grew preoccupied with the possibility that the police might barge into the bureau one day and carry off my computers and papers. This was a stabbing fear, the plundering of decades of journals and unpublished work, but I felt there was no way to protect myself. My life was physically contained and circumscribed by the fortress of the Russian state. I worked and slept in a Russian government compound designated for foreigners — an architectural and organizational holdover from the Soviet Union. I would be naïve to think I had a door that Russians couldn’t unlock.

All communication lines passed through a basement office manned by Russian bureaucrats whose precise jobs I never heard explained. I felt exposed when I passed them smoking cigarettes on the sanded ice of the courtyard.

Life in the compounds was punctuated by ostentatious intrusions: household items conspicuously rearranged, computer files left open, alarm clocks reset to go off in the middle of the night. It was considered gauche to broadcast these events, though, because we reporters were not the story we’d come to cover.

Now I suspect that, by our self-effacing silence, we failed to communicate a fundamental truth of our assignment.

A few days before Christmas, I got a summons from the Ministry of Internal Affairs. On stationery emblazoned with the double-headed eagle, I was instructed to come to the police station. In a note to my bureau, officials said a complaint had been filed by Mr. Lugovoi against Mr. Nemtsov for spreading “slanderous information about him related to an accusation of committing a serious crime.” The government was investigating Mr. Nemtsov and it wanted me to help.

Until then, I’d considered myself basically exempt from interference. Even when I was getting threatening phone calls after writing a profile of the Chechen leader, Ramzan Kadyrov, I had no illusion that I was worth the trouble of attacking. The people who got hurt were Russian heroes — reporters, human rights investigators, dissidents.

I’d never considered the possibility that they might simply ring the doorbell with a piece of paper.

*

I was questioned at a sprawling maze of a police station. The policewoman inquired about my editors and interview method. Again, she demanded my notes. Again, I refused.

I asked if we were finished.

The Man spoke up: “We haven’t started yet.”

The drab office stood next to the Butyrka prison, a landmark that has been stamped deep into the Russian imagination as a ruthless way station for political prisoners since the day of the czars. More recently, Sergei Magnitsky, a young tax adviser who accused police investigators of fraud, had died in a squalid cell, denied treatment for pancreatitis. The United States would eventually impose sanctions targeting Russia in his name.

“The famous prison in which Magnitsky died,” The Man said now. “You can see it outside the window.” He smiled malignantly.

Nobody had introduced The Man. He was dressed in bland street clothes. Everybody deferred to him.

I looked out the window at the prison where Mr. Magnitsky died.

“It’s pretty,” I said.

I kept the recording of that interrogation. It captures the banality and listlessness that can fill a room even when it heaves with muffled danger. The stupor of time, the undecided human messiness of it all. Let’s suck tea through a sugar cube and tell some jokes and decide whether we should crush you. Long, rustling pauses. The tapping of keys.

The police investigator explained that both Mr. Nemtsov and Mr. Lugovoi had already been questioned.

“Did Boris Nemtsov acknowledge what he said?” I asked the investigator.

“Allow me not to answer,” she said.

“I’m just curious,” I said.

“It’s clear that you are curious,” she said.

The Man was growing impatient with me.

“You have to testify because if you refuse to testify then tomorrow or the day after tomorrow, some people may say that what is written in the paper does not correspond to reality,” he said.

“If I had made a mistake,” I told him. “I would have corrected it in the paper.”

The man mused aloud, discussing Gregory Peck, then suddenly turned to me: “Will you put Nemtsov behind bars?”

I said nothing.

“Don’t listen to me,” he said. “I like to joke.”

It was all a joke, except it was not a joke, except it was, except it wasn’t.

They typed my answers, and I signed the pages and went home. I no longer deluded myself into thinking such things ended neatly. I’d been offered a post in China by then; I left as unobtrusively as possible.

Several years later, Mr. Nemtsov was shot in the back just outside the Kremlin walls. He’d been out to dinner with his girlfriend; he was headed home. He was preparing to lead another protest. Last Sunday marked seven years since his assassination.

Mr. Lugovoi still sits in the Duma. Mr. Nemtsov would probably not be surprised to learn that Mr. Putin is now waging war on the entirety of Ukraine.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.