The parenting method RIE — that stands for Resources for Infant Educarers and is pronounced “rye” — and its most famous practitioner, Janet Lansbury, are having another high-profile moment, with interviews this year by Ezra Klein in The Times and Ariel Levy in The New Yorker. And because I’m old and cranky and have been on the parenting beat for a minute, my gut response to this resurgence is: Again? I remember RIE’s previous moments in the sun, with features in Vanity Fair in 2014 and The Daily Beast in 2017.

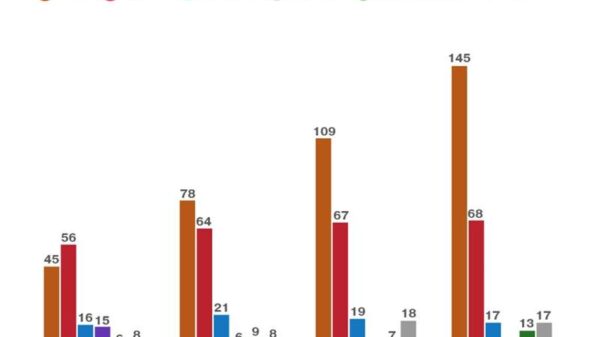

“At its core,” Klein explained, “RIE simply says to view children, even infants, as whole people and to treat them with respect.” The idea, in other words, is to listen to our children and allow them to lead the caregiving process. Meanwhile, fuzzily defined approaches continue to be popular, with #gentleparenting (1.3 billion views) and #respectfulparenting (430 million views) percolating on TikTok, and seem to take some cues from RIE but also freestyle into a sort of open-source mélange, interpreted and remixed by moms across the country.

Gentle or respectful parenting sounds great — after all, who doesn’t want to be gentle and respectful to our children? But then you get into the details of RIE, and they are quite prescriptive. As The Daily Beast put it, “It has its own tight-knit circle of instructors; its own rituals (the narration of the diaper change); its own spare aesthetic (no mirrors, no dangling mobiles, no Baby Einstein); and its own set of guidelines (no singing, no rocking, no playpens). All of this honors the baby’s ‘struggle’ and builds a more ‘authentic self,’ proponents believe.”

It’s well meaning but also pretty time intensive and maybe a bit dour. (As one Twitter wit put it to me, “Are there inauthentic children?”)

I’m not trying to pick on RIE in particular. Other philosophies have trended semi-recently: free-range parenting, French parenting and tiger parenting, to name a few. If you find RIE or any of these other methods beneficial to your kids and it makes you feel more confident and less agitated as a parent, that’s fantastic, and you should keep using them. But having read parenting literature for years, having seen trends come and go and having witnessed the individuality of my own kids and their peers and the differences in their family situations, I’m confident that there are numerous ways to raise thriving kids without cleaving precisely to one particular parenting dogma.

The broadest agreement among experts is that what works best is authoritative parenting, described by the American Psychological Association as parenting that is “nurturing, responsive and supportive” yet at the same time sets firm limits and boundaries. But there are probably a million ways to authoritatively parent that can be inclusive of and borrow from many styles or methods or none at all.

I would categorize the two main styles of parenting advice as either trying to control a parent’s behavior or trying to control a child’s behavior. RIE and gentle parenting fall into the former category; they’re all about letting the child lead the process. For example, Lansbury believes that children don’t need toilet training and that instead you should model toileting, give them the choice between diapers and underwear and not give rewards for going potty. The aim, Lansbury says, is to trust that children will let you know when they are ready. Parent-led methods, like the one suggested by Nathan H. Azrin and Richard M. Foxx in their book “Toilet Training in Less Than a Day,” involve positive reinforcement. The idea here is that parents can potty train on a much shorter timetable using a variety of rewards like cool underwear as a bribe to encourage a child to get out of diapers.

There isn’t much strong research on potty training, but the research that exists shows that both methods work fine and that your child’s temperament and your family circumstances matter in which one you choose. In my experience, the parent-led method worked better with my older daughter, and the child-led method worked better with my younger daughter. But the point isn’t the specific issue of potty training as much as it is that there isn’t a one-size-fits-all way to approach most components of the child-raising process.

My concern with people’s reliance on any one parenting method or philosophy is that it can set them up for feeling a sense of failure or inadequacy if it doesn’t pan out the way they hoped and leads them to think that they’re not doing it “right,” whatever parenting “right” means. “I often lurk in some social media parenting groups for my own research or to see what parents are struggling with,” Christopher Willard, a psychologist and author, wrote to me in an email. “Depressingly, like much social media, what I keep encountering is a cesspool of bullying and parent shaming and extreme interpretations of the kindest, gentlest approaches to parenting. Highly ironic for groups that purport to be about compassion.” He added that in his family practice he spends time with parents “who have been bullied right out of parent support groups for not toeing the line.”

Many of the highly defined parenting methods seem to promise that if you follow them to the letter, you’ll feel an end to the routine frustrations of parenting. That’s certainly a thread running through many of Lansbury’s podcasts: “How to Stop Feeling Frustrated by Your Child’s Behavior — A Family Success Story,” boasts one title. “We want to help her avoid getting frustrated with him because that doesn’t feel good to her or to him,” goes another nugget of guidance.

Most parents know deep down that you can’t avoid feeling frustrated or annoyed by your children. Frequently. As the psychotherapist Rozsika Parker argued in her book “Torn in Two,” “Maternal ambivalence is the experience shared variously by all mothers in which loving and hating feelings for their children exist side by side.” This ambivalence, she wrote, “is normal, natural and eternal.”

“The representation of ideal motherhood,” Parker continued, “is still almost exclusively made up of self-abnegation, unstinting love, intuitive knowledge of nurturance and unalloyed pleasure in children.” Many of the most popular parenting philosophies seem to imply that if we just try hard enough, if we just listen to enough podcasts, read the right books and follow the right scripts, we’ll find that promised land of unalloyed pleasure. But it’s a fantasy that doesn’t allow mothers, especially, the full range of human emotions. Every single day, you might feel frustration, rage, deep love, wistfulness and boredom, and sometimes you’ll feel a complicated mess of these feelings — none of which make you a “good” or “bad” parent.

While fathers certainly feel some of these pressures, there is more cultural room for paternal ambivalence. Recall, for instance, that when Adam Mansbach’s wryly vulgar children’s book for adults became a pop phenomenon a decade ago, many mothers grumbled that if a woman had written a bedtime story with a four-letter word in the title, it would have landed much differently.

We seem destined to keep struggling with acceptance of ambivalence on a very basic level, illustrated by the fact that in 2022, there is someone on Reddit still asking, “Is putting your child in day care full time really as bad as everyone says it is?” That we’re still trying to convince people that not spending every minute of the day with your child isn’t destructive means we have a very, very long way to go.

How would you describe your personal parenting philosophy? Tell me about it in the comments.

Want More on Parenting Philosophies?

-

In The New Yorker, Jessica Winter has an excellent profile of Maria Montessori, the Italian educator whose early childhood education philosophies are widely influential, particularly among private preschools.

-

The opposite of RIE parenting might be snowplow parenting, in which parents push every obstacle out of their child’s path to success.

-

In 2020, I combed through a century of parenting advice in the archives of The Times and found that so much of it was, and is, trend-based and circular. “In 1890 women’s magazines recommended ‘loose scheduling’; in 1920 they were all for the tight schedule, ‘cry it out’ routine, and in the last year analyzed, 1948, all were for ‘self regulation’ by the baby,” according to a Times article from 1952. Same as it ever was.

Tiny Victories

Parenting can be a grind. Let’s celebrate the tiny victories.

My 8-year-old tested positive for the coronavirus on her brother’s 11th birthday, and her first thought was concern that it might ruin her brother’s birthday. His reaction to having his plans canceled was to ask if we could write “Feel better!” on half of his cake to make it special for her, too.

— Heather Osterman-Davis, New York City

If you want a chance to get your Tiny Victory published, find us on Instagram @NYTparenting and use the hashtag #tinyvictories; email us; or enter your Tiny Victory at the bottom of this page. Include your full name and location. Tiny Victories may be edited for clarity and style. Your name, location and comments may be published, but your contact information will not. By submitting to us, you agree that you have read, understand and accept the Reader Submission Terms in relation to all of the content and other information you send to us.