Last June, a meeting of the Dutchess County Legislature in New York’s Hudson Valley quickly turned heated over how to spend some of the county’s $57 million in federal pandemic relief aid.

For more than two hours, residents and Democratic lawmakers implored the Republican majority to address longstanding problems that the pandemic had exacerbated. They cited opioid abuse, poverty and food insecurity. Some pointed to decrepit sewer systems and inadequate high-speed internet. Democrats offered up amendments directing funds to addiction recovery and mental health services.

In the end, the Legislature rebuffed their appeals. It voted 15 to 10 to devote $12.5 million to renovate a minor-league baseball stadium that’s home to the Hudson Valley Renegades, a Yankees affiliate.

“Who created this plan? Some legislators?” asked Carole Pickering, a resident of Hyde Park. “These funds were intended to rescue our citizens to the extent possible, not to upgrade a baseball field.”

“I think we should be a little bit ashamed,” Brennan Kearney, a Democrat in the Legislature, told her fellow lawmakers.

Cities and counties across the United States have found themselves in the surprisingly uncomfortable position of deciding how best to spend a windfall of federal relief funds intended to help keep them afloat amid deadly waves of Covid-19 infections.

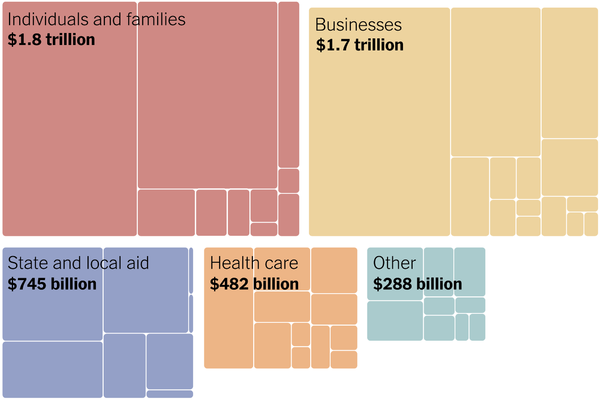

The pandemic, which is showing signs of waning as it enters its third year, prompted the largest infusion of federal money into the U.S. economy since the New Deal. President Biden and former President Donald J. Trump got Congress to approve roughly $5 trillion to help support families, shop owners, unemployed workers, schools and businesses.

A large portion of the aid went to state, local and tribal governments, many of which had projected revenue losses of as much as 20 percent at the pandemic’s onset. The largest chunk came from Mr. Biden’s $1.9 trillion recovery bill, the American Rescue Plan, which earmarked $350 billion. That money is just beginning to flow to communities, which have until 2026 to spend it.

“We’ve sent you a whole hell of a lot of money,” Mr. Biden said during a meeting with the nation’s governors in January.

In many cases, the money has become an unusually public and contentious marker of what matters most to a place — and who gets to make those decisions. The debates are sometimes partisan, but not always divided by ideology. They pit colleagues against each other, neighbors against neighbors, people who want infrastructure improvements against those who want to help people experiencing homelessness.

“It’s both breathtaking in its magnitude but it still requires some hard and strategic choices,” said Brad Whitehead, who is a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Metro, a metropolitan policy project, and advises cities on how to use their funds. “One of the difficulties for elected leaders is everyone has a claim and a thought for how these dollars should be used.”

Local governments were given broad discretion over how to use the money. In addition to addressing immediate health needs, they were allowed to make up for pandemic-related revenue losses from empty transit systems, tourist attractions and other areas that suffered financially.

That money is often equivalent to a third or nearly half of a city’s annual budget. St. Louis, for instance, will receive $498 million, more than 40 percent of its 2021 budget of $1.1 billion. Cleveland, with a city budget of $1.8 billion, will get $511 million.

But the relief comes with strings: Governments are prohibited from using the funds to subsidize tax cuts or to make up for pension shortfalls. And because the aid is essentially a one-time installment, it wouldn’t necessarily help cover salaries for new teachers or other recurring costs.

Several states have sued the Biden administration over the tax cut restriction, claiming it violates state sovereignty. Some governments have refused to take the money over concerns that it would give the federal government power to control local decision-making.

In Saginaw, Mich., the mayor formed a 15-person advisory group to recommend ways to spend the city’s $52 million allotment. Harrisburg, Pa., which received $49 million, has held public events seeking input from residents. Massillon, Ohio, identified the biggest source of public complaints — flooding and sanitation issues — and proposed using its $16 million share to address those areas.

“We listened to the people, and we’re trying to make improvements for them,” said Kathy Catazaro-Perry, Massillon’s mayor. “Our city is old. We have a lot of areas that did not have storm drains, and so for us, this is going to be huge because we’re going to be able to rectify some of those older neighborhoods.”

But many have found their communities mired in clashes over who has the power to spend the money.

In New York’s Onondaga County, which includes Syracuse, legislators from both parties have been trying to claw back spending authority from the county executive, Ryan McMahon, a Republican.

When the first half of the county’s $89 million stimulus share arrived last spring, Mr. McMahon placed it into an account that he controlled and began committing funds to projects, including a $1 million restaurant voucher program, $5 million in incentives for filmmakers to produce in the area and $25 million for a multisport complex featuring 10 synthetic turf fields.

Lawmakers, who questioned why they were not being asked to vote on the spending, were told by the county attorney’s office that they had ceded that authority in December 2020 when they approved an emergency resolution that gave the county executive authority “to address budget issues specifically related to Covid-19 global pandemic.”

Legislators argued that they had never intended for that control to extend beyond the immediate pandemic response.

James Rowley, who was elected chair of the Onondaga County Legislature in January, hired a lawyer and spent $11,000 preparing a lawsuit to challenge Mr. McMahon.

“We have the power of the purse,” Mr. Rowley, a Republican, said in an interview. “I didn’t want to set a precedent that gave the county executive power to spend county money.”

Mr. McMahon did not respond to a request for comment. On Feb. 22, he sent a letter to the Legislature proposing that it regain control of the stimulus funds that had not yet been allocated.

“I recognize your concern,” he wrote, noting that “our cooperative actions should comport with county charter principles of separation of powers.”

The rush of money from the federal government is in part an attempt to avoid the mistakes of the last recession, when state and local governments cut spending and fired workers, prolonging America’s economic recovery. But analysts say it will take years to fully assess whether all the spending this time was successful. Critics argue that the overall $5 trillion effort has added to a ballooning federal deficit and helped propel rapid inflation. And many states report increasing revenue, and even surpluses, as the economy strengthens.

The money has led to ideological fights over the role of the federal government.

In January, dozens of residents crowded into a City Council meeting in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, where they demanded that the mayor and other officials turn down the city’s $8.6 million share of stimulus funds, saying it was a ruse by Washington to take control of the town.

Residents booed and called the Council members “fascists.” Several referred to the money as a Trojan horse, lamenting that taking it would allow the federal government to impose restrictions on Idaho, including establishing vaccine checkpoints. Amid cries of “Recall!” one woman shouted repeatedly that “you have given up our sovereignty.”

“Nobody wants this money,” Mark Salazar, a resident, said to applause. “I don’t want to be under the chains of the federal government. Nobody does.”

The council eventually voted 5 to 1 to accept the funds, saying they would go toward expanding a police station and other areas.

Dutchess County residents were similarly agitated, if less rowdy, at their June 14 meeting about the stadium. Guidance on using the funds issued by the Treasury Department specifically cited stadiums as “generally not reasonably proportional to addressing the negative economic impacts of the pandemic.”

So why, those in attendance asked, was this happening?

Marc Molinaro, the county executive, defended the spending, saying Dutchess County had identified $33 million in lost revenue as a result of the pandemic and that, according to the Biden administration’s guidance, stimulus funds could indeed go toward investing in things like the stadium.

“It’s basically any structure, facility, thing you own as a government, you can invest these dollars in with broad latitude,” Mr. Molinaro said.

In a recent interview, Mr. Molinaro said that because the funds were one-time money, the county needed to be careful not to create expenses that could not be paid for once the federal funds ran out.

He added that investing in the stadium would produce an ongoing revenue stream for Dutchess County — money that he said would allow the government to pay for the types of programs that Democrats wanted.

The investment, he said, “allows us to create 25 years of revenue that we can invest in the expansion of mental health services, homelessness and substance abuse.”

That explanation has not mollified everyone.

“I was just devastated that we spent the money that way,” Ms. Kearney, the Democratic legislator, said in an interview. “It was such a betrayal of our community. So grossly inappropriate and grossly tone deaf to the needs of the people in Dutchess who have suffered.”