César Franck’s only symphony was a pillar of the repertory for decades. But it’s now a rarity.

Whatever Leopold Stokowski’s thirst for celebrity, he was not known for caving to audience pressure. During his long tenure conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra, from 1912 to 1938, Stokowski gave the American premieres of scores as challenging as Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring” and Berg’s “Wozzeck,” with little concern for box office.

But near the end of most of his seasons in charge, this great showman did bow to mass taste. Philadelphia’s subscribers were invited to vote for their favorite works, with the promise that Stokowski would lead the winners on a closing “request program.”

For years, the victor was Tchaikovsky’s “Pathétique,” a sorrowful symphony so popular that other orchestras had been, the critic Lawrence Gilman wrote in 1925, “so sure of the outcome of similar voting contests that they sent their programs to press before the date of the election.”

But at the end of the 1923-24 season, a challenger dealt the Tchaikovsky a knockout blow: César Franck’s Symphony in D minor.

“Is it inflating the symphony of the lovable Belgian,” Gilman wondered in the New York Herald Tribune, “to rank it above the dolorous swan song of Tchaikovsky?”

Probably, Gilman concluded. But the Franck, which the composer completed in 1888, would not be downed.

Stokowski leading the opening

Philadelphia Orchestra, 1927 (Music & Arts)

“What is there in the texture of the music itself to explain its popularity?” Gilman pondered, reporting another landslide in 1929, when the Franck beat Beethoven’s Fifth, Tchaikovsky’s Fifth and Sixth, and Brahms’s First. In 1924, Gilman had scorned “the more than occasional triteness and inferiority of its musical expression,” and though he admitted that it had an “unforgettably noble distinction of contour and gesture,” it was in his view no match for the greats.

Perhaps, Gilman wrote, “the public taste is itself part of the problem.” Yet, he added, “the interest and the oddity of the verdict remain.”

Quiet, sincere and more famous in his lifetime as an organist and teacher than as a composer, Franck celebrates the bicentenary of his birth this year. But it’s unlikely that American orchestras will bring to the celebration the fervor with which they once performed his sole symphony. In one of the stranger stories in the history of the canon, the work — which from the 1920s until the ’60s was such a hit that the New York Philharmonic thought it a solid bet to fill Lewisohn Stadium on a hot summer’s night — is now all but absent from concert halls.

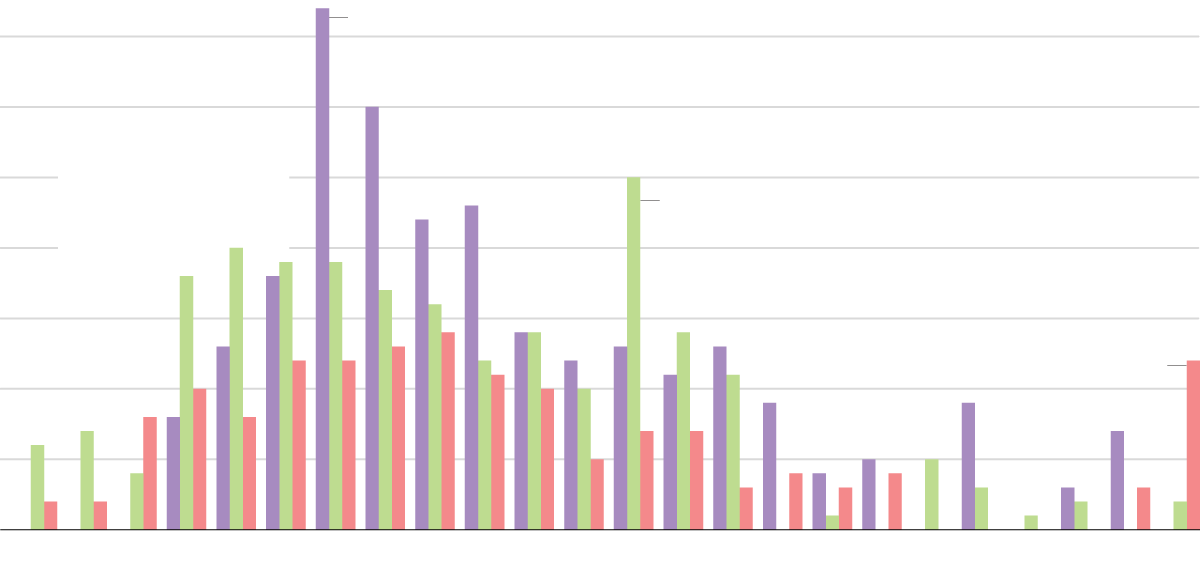

Decline of a Once-Popular Symphony

Premiered in 1889, Franck’s Symphony in D Minor surged in popularity during Germany’s World War I occupation of the composer’s native Belgium. But interest has tapered off in the last 50 years.

“There is a lot of music that at one time was very popular and then disappeared,” the conductor Riccardo Muti said in an interview. Muti recorded the Franck with the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1981 and was the last person to lead it at Carnegie Hall, with his Chicago Symphony Orchestra, in 2012.

“But in the case of this symphony,” Muti went on, “I don’t understand.”

It’s hard now to appreciate the extent of the Franck symphony’s success, which was neither immediate nor brief. Part of the flurry of pieces — including the “Prélude, Choral et Fugue” for piano, a string quartet and violin sonata, and his valedictory “Trois Chorals” for organ — that emerged from the last decade of its composer’s late-blooming career, it had its premiere in Paris in 1889.

Greeted tepidly then, the symphony waited a decade for its American debut, long after Franck had died, in 1890. The Boston Symphony’s performances in April 1899 left critics unsure, too. The Boston Herald deplored its “wearisome repetitions” but noted the “certain weird fascination that it exerts.” The Boston Globe suggested that it was “calculated to appeal more to the educated musician than to the average concert patron.”

Not quite. While the symphony kept up a steady pace of European performances, it took off in Britain and America, where Franck was feted as the musical representative of occupied Belgium during World War I, as his biographer R. J. Stove explains. By the early 1920s, when Franck’s tone poem “Le Chasseur Maudit” and the Symphonic Variations for piano and orchestra were also staples, his symphony had built up such a reputation that its place in the repertory held secure for decades.

From 1926 to 1930, the New York Philharmonic performed the Franck as much as Beethoven’s Fifth; Arturo Toscanini, Pierre Monteux and Willem Mengelberg were among the 12 conductors who led it in that period. Carnegie Hall audiences heard the work six times in 51 days in the spring of 1927, from the Boston Symphony, the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, the New York Symphony Orchestra, and three times from the New York Philharmonic under Wilhelm Furtwängler, who enjoyed the work enough to annex Franck in his writings as a truly German symphonist. (Nazi propagandists did likewise.)

Toscanini leading the first movement

NBC Symphony Orchestra, 1940 (Pristine Classical)

Furtwängler, too

Vienna Philharmonic, 1945 (Deutsche Grammophon)

The variety of conductors who performed the Franck suggests that its longevity came partly from its uncanny ability to withstand a range of interpretations. Set in three movements, it leans heavily on late Beethoven: It borrows from the master’s Ninth Symphony for the colossally abrasive moment of recapitulation in its first movement and in the recall of prior themes in its third, and its opening motif echoes the finale of the last string quartet, the three notes Beethoven labeled “Muss es sein?” (“Must it be?”).

The Franck symphony’s improvisatory structure and its orchestration were often described as organ-like — hardly surprising, given that its composer spent over three decades toiling in church services at Ste.-Clotilde, and as the organ professor at the Paris Conservatory after 1872.

“Soaring lyricism, kaleidoscopic modulations, and spiritual depth reached unprecedented heights with Franck on the organ bench,” Paul Jacobs, who begins a survey of the organ pieces in New York on March 29, said in an email. “These characteristics poured into his other work, including the symphony.”

Besides Beethoven, Franck’s clear reference point in the symphony was Wagner. Many of Franck’s students were adoring Wagnerians, but he was conflicted. The conductor François-Xavier Roth, who leads Franck with the ensemble Les Siècles in Paris in June, said in an interview that in the symphony “you have the fight of inventing or defending a kind of French music against Wagner’s.”

Even so, it was a fight in which Franck borrowed from his foe. Gilman, the Tribune critic, once accused the symphony of “weeping maudlin chromatic tears like an impotent Tristan.”

Was this a French work, then? German? The height of Romanticism? The counterattack of Classicism?

Recordings suggest that conductors answered “all of the above,” and the work emerged unscathed regardless. Furtwängler gave it Wagnerian stakes; Herbert von Karajan and Eugene Ormandy swamped it in sound; Stokowski and Leonard Bernstein toyed with it, and the score didn’t particularly mind. Monteux, who heard the work’s premiere as a boy and was asked to perform it so often that in 1949 he said he was “tired to death” of it, nonetheless did it with the Chicago Symphony in 1961 with his typical, graceful energy, leaving one of the finest records ever made.

Karajan conducting the first-movement recapitulation

Orchestre de Paris, 1969 (EMI)

And Bernstein

Orchestre National de France, 1981 (Deutsche Grammophon)

And Monteux

Chicago Symphony Orchestra, 1961 (Sony)

Since Monteux’s landmark, there have been more performances and recordings, especially from Francophile conductors, but the symphony never recovered its omnipresence. The New York Philharmonic performed it in all but two calendar years from 1916 to 1964, but has offered it in only 12 of the years since — and not at all since 2010, when Muti was on the podium.

So where did the Franck go?

“It was often played in a very superficial way,” Muti said, “so I think that at a certain point, the public had had enough.”

Not just the public: Muti added dryly that over the course of the Chicago Symphony’s tour with the piece in 2012, he came to feel that “the musicians preferred other things.”

Deadening routine is part of the answer, as is the work’s relative simplicity for an orchestra, which might be perceived as a shortcoming in an era that has placed ever more stock in musical complexity and virtuosity. But neither routine nor straightforwardness has harmed other war horses.

Did it lose out as its champions passed from the scene? That might have been the case in Boston. Charles Munch, a fiery Franckian, took the Boston Symphony’s Francophilia with him when he left in 1962; Franck’s decline there corresponds with the rise of Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra, a Boston commission that its more recent conductors have touted like the trademark the Franck had been. But the Franck had not really seemed to depend on a small circle of advocates, and no single work has replaced it everywhere.

Another common suggestion is that the Franck’s spirituality — the critic Olin Downes described the processional slow movement, with its English horn solo, as “a religious meditation like none other in music” — became less relevant in a more secular age, one in which the earthly anxieties of Mahler and Shostakovich seemed more apt. But that hasn’t hurt Bruckner.

Another thought might be that as the canon changed around it, the Franck seemed to have less to say contextually. Franck had his imitators, certainly, but his symphony was a bit of a dead end. It’s telling that Pierre Boulez, at the New York Philharmonic from 1971 to 1977, was its first music director since Mahler not to perform the work.

Berlioz aside, Boulez made the influential choice to begin his French repertoire with Debussy — who briefly studied with Franck but grew distant from his teacher’s influence, snarking in 1913 that Franck “was unaware of boredom” — and Ravel, who heard in the symphony “daring harmonies of especial richness, but a devastating poverty of form.”

And if newer music by the likes of Sibelius and Stravinsky pushed the Franck aside — although not brand-new music, which American orchestras have played less of over time — the past also struck back. The Boston Symphony has performed Dvorak three times as often in the second half of its history as in its first, according to the orchestra; Mozart’s fortunes have risen almost as dramatically.

The ending, led by Monteux

Chicago Symphony Orchestra, 1961 (Sony)

Facts like that convey the lasting conservatism of much of the orchestra world, and they make it hard to argue too strenuously that the Franck should be resurrected. The righteous call now is to diversify what ensembles play, in all senses of the verb. Inevitably, some works will rise to prominence in the process, and some will drift away.

And if that’s the moral of the tale, it’s all right. The rise and fall of Franck’s symphony shows that the canon can change — that the canon can be changed.